London Fiction: Up The Junction

Nell Dunn's early 1960s short stories remind us that in some ways it's a blessing that things ain't what they used to be

I’ve been conscious of Nell Dunn’s Up The Junction as a book, a TV Wednesday Play, a film and a sort of shorthand for a strand of 1960s London life since being a young child growing up far away. They formed part of the London of my imagination.

Later, Dunn’s title was attached to a pop song inspired by the same south London milieu. That song, a beautifully-realised musical vignette by Squeeze released in 1979, is probably why I bought a 1966 paperback edition of Dunn’s 1963 book from some charity shop, or market stall, or whatever, somewhere or other long ago.

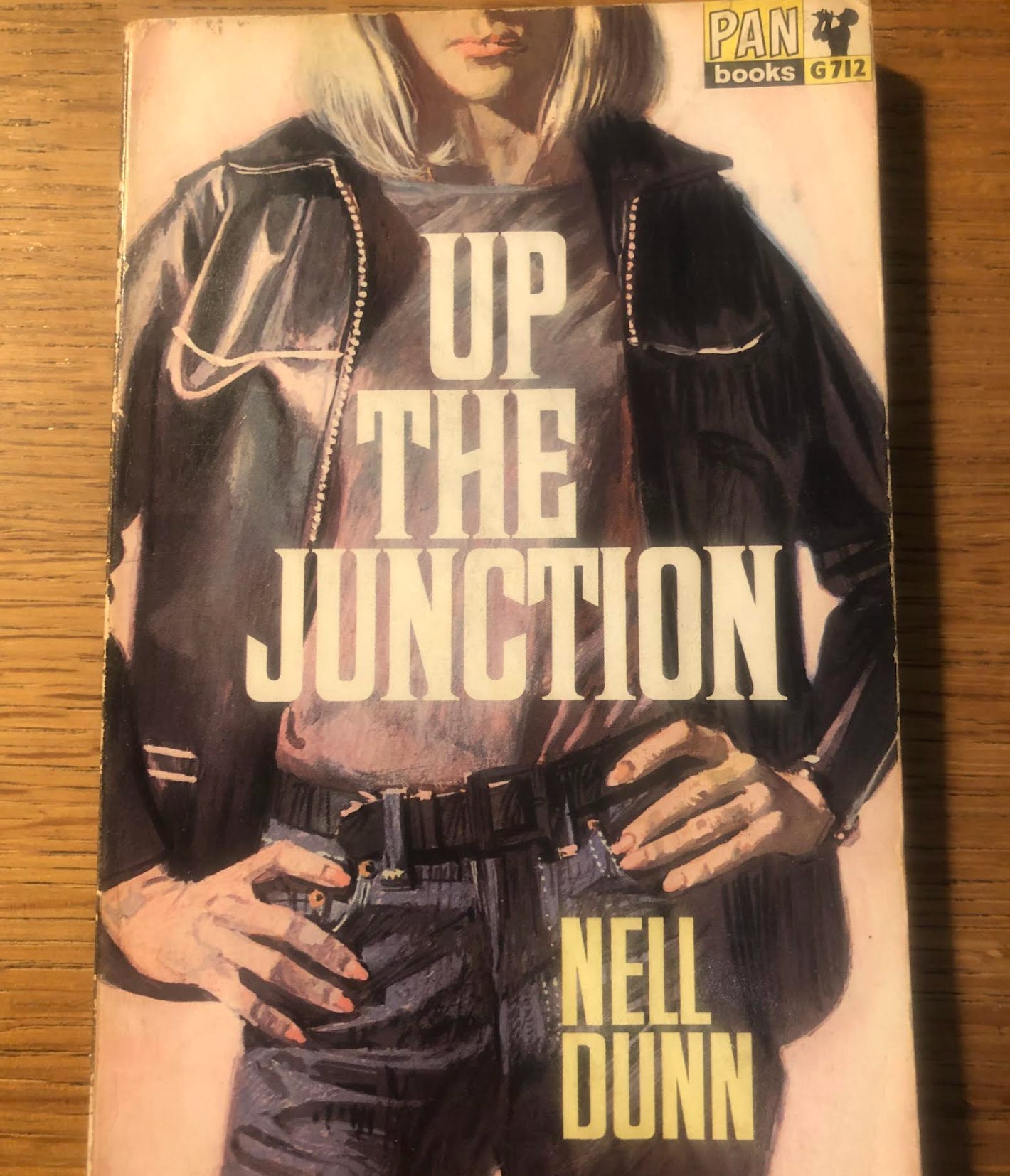

Since whenever that was, the book has been kicking around on my shelves, cherished as a piece of vintage pop culture design but never actually read from beginning to end - and here I sense your anticipation soar - until now.

I’m going to tell you first of all that it’s depressing. I don’t mean the observational insights of Dunn’s spare yet vivid prose or everything about her cast of Battersea characters, women, especially young women, to the fore. I mean the slum landscape they inhabit and endure: slum housing, slum prospects, slum lives with little hope of transcending them, for all their energy and appetite for experience, love and joy.

Rough boys with motorbikes feature strongly, offering escape and adventure, sexual and otherwise. So do smashed marriages, crime, grime and debt. Utterly up-to-date in its time, Up The Junction is an antidote to nostalgia today.

Dunn’s background was posh: daughter of a knight, granddaughter of an earl. London-born, she married Eton-educated Jeremy Sandford, later the screenwriter of Cathy Come Home, and, in 1957, they moved together downmarket from Chelsea to what was then a very different Battersea from today’s.

Dunn got a job in a sweet factory, made friends and turned her experiences into stories, in which she, or a version of her, appears as participant and observer:

“Dignified, the three of us squeeze between tables and sit ourselves, knees tight together, daintily on the chairs.

‘Three browns, please,’ says Sylvie before we’ve been asked.

‘I’ve seen you in here before, ain’t I?’ A boy leans luxuriously against the leather jacket slung over the back of his chair.

‘Might ‘ave done.’

‘You come from Battersea, don’t yet?’

‘Yeah, me and Sylvie do. She don’t though. She’s an heiress from Chelsea.’”

The stories move from beehives and fake tans and cheap high heels a size too big to tally men and clip joints and tarts up the spout and dead foetuses flushed down the toilet. The final one sketches Battersea children amid “torn buildings and mud swamps scattered with bricks and floating newspapers”.

As with Muriel Spark’s The Ballad of Peckham Rye, published three years earlier, the war and its legacy are alluded to but never quite mentioned - still too adjacent, maybe. Swinging London was arriving, but the King’s Road feels far away.

The expression “up the junction” meant being in deep trouble. In Dunn’s Battersea it was on the doorstep, like it or not, every day.

Order Up The Junction from my local bookshop Pages of Hackney. Order my London novel Frightgeist from there too. Read about The Wednesday Play adaptation here. Watch a clip of the film version here and read about that here. Watch the video of Squeeze performing their song Up The Junction here and read about that here.

I have a mission to read and write about 25 pieces of London fiction in 2024 I haven’t read properly before. Up The Junction was one of them.