London Fiction - Oliver Twist

Charles Dickens's second novel maps the social geography of Victorian London and draws a contrast between the depravity of its criminal underworld and the wholesomeness of the countryside

I’ve set myself the task for 2024 of reading and then writing about 25 pieces of London fiction I haven’t read before. This is number 14 in the haphazard series.

Here’s Bill Sikes, that rotten wrong ‘un, chivvying our young hero across town to be his reluctant partner in crime:

“Turning down Sun Street and Crown Street, and crossing Finsbury Square, Mr Sikes struck, by way of Chiswell Street into Barbican: thence into Long Lane, and so into Smithfield; from which latter place arose a tumult of discordant sounds that filled Oliver Twist with amazement.”

This is one of the most vivid depictions of London in Charles Dickens’s second novel, originally published as a serial from 1837 to 1839. In the meat market:

“The ground was covered, nearly ankle-deep, with filth and mire; a thick steam, perpetually rising from the reeking bodies of the cattle, and mingling with the fog, which seemed to rest upon the chimney pots, hung heavily above.”

Soon, they are in Holborn, still on foot, and checking the time by St Andrew’s church. On they go, Sikes forcing Oliver to trot to keep up, all the way past Hyde Park Corner and heading on to Kensington before hitching a horse-and-cart ride to Isleworth en route to a botched house-breaking in Chertsey.

A lot of the story, including the workhouse scenes, takes place outside London and much of what occurs within it unfolds in the dark and filthy interiors where Fagin, the most famous of the novel’s many villains, plots, wheedles and counts his gold. “The Jew” as he is routinely referred to – cementing an antisemitic portrayal Dickens would later regret – has an intimate knowledge of the backstreets of Bethnal Green and has his lair in Field Lane at the bottom of Saffron Hill, just west of where Farringdon Road would soon be built above the River Fleet.

This is where Jack Dawkins, the Artful Dodger, leads a runaway Oliver, having cunningly taken him under his wing in Barnet. Dickens maps the social geography of the capital of 200 years ago: a sharp west-east divide; a respectable Pentonville, where Mr Brownlow, Oliver’s first and steadfast patron resides; and the Angel, which is perceived another villain, the bullying coward Noah Claypole, hoping to make his criminal fortune in the capital, as “where London began in earnest”. From there Noah, progressed to St John’s Road, and it was all downhill from there:

“…deep in the obscurity of the intricate and dirty ways, which, lying between Gray’s Inn Lane and Smithfield, render that part of the town one of the lowest and worst that improvement has left in the midst of London.”

Dickens depicts Victorian London in Oliver Twist at its harshest, cruellest and most morally lost. He could hardly draw a sharper contrast between it and the countryside backdrops where Oliver finds another escape from the urban vice and exploitation Fagin and Sikes personify. Did he actually like the city in which so much of his fiction is set? Perhaps, like others inspired by it, his feelings were productively mixed.

The novel as a whole displays the well-documented qualities of Dickens’s writing: his lampooning of pomposity, his eye for hypocrisy, his searing indictments of greed and cruelty, and his sometimes extreme sentimentally. Oliver himself is more ideal type than fully-formed character, a boy with an angelic nature so robust it seems wholly unaffected by the neglect and brutality he has endured since birth.

The plot depends on a series of coincidences, any one of which would be astounding in real life. Still, Dickens was an entertainer as well as a commentator and observer, and no one can say he didn’t find an audience or make his point. Oliver Twist is the first Dickens novel I have properly read, and it taught me a lot.

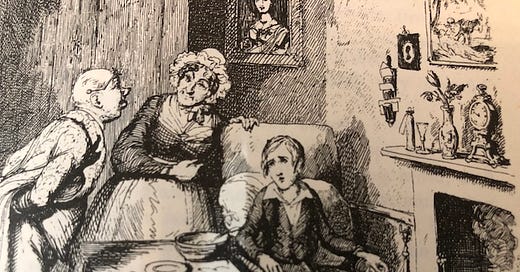

Buy John Vane’s London novel Frightgeist from On London, from Pages of Hackney or from Amazon. John Vane is a pen name used for fiction and fun by On London publisher and editor Dave Hill. Image: George Cruikshank.